| Friday, October 17, 2003 |

11:58 - Come on in, there's plenty for all

|

(top)  |

Yesterday was a very important milestone for Apple.

For years, people have been asking, "If Apple's software is so great, why don't they just port it to Windows?" And "All Apple has to do is bring out Mac OS X for the PC platform. That's where all the money is! Right?"

It's kinda like saying, "Well, if the reason we went to war is weapons of mass destruction, then where are they?" A question a child might ask, but not a childish question. Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Huhhh. Anyway... as I said last April:

Lance used to work for a company called WorldTalk. Back in the mid-90s, WorldTalk had a killer app: an e-mail gateway server package that could translate between just about any of the dozens of proprietary e-mail formats that were in use at the time, in the pre-Web, pre-online-desktop Internet. Companies using cc:Mail could talk to companies using Lotus Notes could talk to companies using SMTP could talk to companies using MS Exchange. All you had to do was buy the WorldTalk gateway, which cost $70,000 and ran on an HP-UX machine which the company preconfigured for you and included in the deal.

It was ingenious, and it worked great. The software included translators for each of the mail systems that would preserve the maximum common formatting that both the sender and the recipient could handle, and it would translate everything in a bidirectional way so that nobody would ever know there was a middleman. To a cc:Mail sender, WorldTalk looked like a cc:Mail server. To an Exchange client, it looked like an Exchange server. They sold all kinds of copies and were making a killing.

Of course, this was in the days before good ol' SMTP mail grew to account for slightly over 100% of Internet e-mail traffic. This consolidation killed off cc:Mail, Lotus Notes, and all the little proprietary competitors one by one. And obviously WorldTalk's market was going to go away eventually.

But whether or not this consolidation would have ever really caused the destruction of WorldTalk through the complete deflation of their business plan is a side issue and now a moot point.

Because, you see, the WorldTalk execs made an odd decision back in about 1996: They figured, hey-- there's this new platform called Windows NT. It's cheap, it runs on any PC-- why don't we produce a cut-rate version of our software that runs on NT, includes only the most popular translators, and costs only $700? That's only one-hundredth the cost of the full standalone HP-UX package we sell right now. Sure, we'll lose some HP-UX customers, but the NT market will explode!

So they did. They sold an NT version of their gateway software that cost $700. And by God, they sold ten times as many copies.

WorldTalk was dead within a year.

So it is with Apple. If they were to port Mac OS X to the PC, they'd never sell a Mac again-- and their margins would plummet to a tiny fraction of what their business plan and stockholders expected. They can't give up the Mac platform, and they can't give away the keys to it. Doing so would kill Apple.

It's up to the company to come up with new ways to leverage the Mac platform itself, sell more boxes, and seek out market tie-in opportunities that bring in revenue that's both a supplement to and enhanced by being linked to a Mac.

Like, oh, say, the iPod.

Sure, it's got its competitors. But now that it's been revealed as a full-fledged digital lifestyle device, not just a MP3 player-- and not, critically, just another PDA, which is a solution that's always struggled to find a problem to solve-- it's still really in a class all its own.

When it first came out, it was criticized for its high price, but more so for its Mac exclusivity. "Wow, it's really cool. Whaddya mean, it's only for the Mac?" Bill Gates reportedly said while trying one out. But Apple knew what it was doing. It had iTunes, which was already one of the best "showcase" applications the Mac had ever seen; anybody looking for a prime example of Apple's reserved and elegant design sense, of form following function and everything in its proper place, needed to look no further than iTunes. It's one of those programs where you look around, you click on things, and you feel overwhelmed by this sense of general software well-being, of everything being exactly where it should be, like it was designed according to ley lines or Feng Shui or something, to the point where you just can't picture any of the controls or interface elements being laid out any differently. And in the face of its competition-- like MusicMatch, which looks inexplicably like a car radio, complete with chrome and LCD-like displays, and WinAmp, which everybody loves for its skinnability but which contains no real cataloging or ratings or device-syncing capabilities-- it feels like the island of sanity amid a sea of confusion. It's the Mac's crown gem.

And the iPod was designed to be "iTunes to go". The same intuitiveness of interface, the same rules to follow when you seek out your music. You see, many companies have good UI design practices. Everybody has a set of standards that they try to live up to. But one thing that Apple does, that I don't think I've seen anybody else even try to hold themselves to, is design their products so that everything is equal. They strive to make sure that no feature is left behind, that there are no annoying exceptions to deal with; while the iPod was missing any features that iTunes had, or vice versa, fixing those inequities was always foremost on Apple's agenda for new versions of the software. Consistency. Predictability. That's what good design is all about, and Apple focuses on it sometimes to the exclusion of critical bug fixes, which can be both an asset and a detriment.

All you have to do is look at the various music stores for an illustration of the Apple philosophy: BuyMusic.com advertises "79 cents a track", but if you actually go into the site and look around, you find that there are maybe like six songs in the whole site that are 79 cents, and the rest are priced anywhere from 99 cents to $2.00. And every album has different rules for how many times (or whether) you can burn it to a CD; BuyMusic.com didn't bother itself with doing all the bending-over-backward negotiation involved in signing every label to an identical set of terms, so they just threw everything together, each artist and label with its own terms, and let the buyer figure it out. And apparently they're paying the price for it, as most customers find the site completely infuriating for that very reason. PureTracks.com, similarly, advertises "99 cents a track", but that only seems to apply to the featured tracks linked off the site's main page-- all the rest are $1.19 or so. What's a customer to do?

But Apple knew that the key was to put the onus on the labels, to drive the complexity into the back-end as it were (just as they aspire to do with their software), and do what it took to get everybody to sign to the same terms. 99 cents a track. $9.99 an album. Everybody, no exceptions. Big label? Small label? Doesn't make a difference. You could be BMG, or you could be Bob's Podunk Label-- doesn't matter; you sign the contract, you submit your music, you're held to the same rules. (If an album is of a weird size or format-- really long or really short tracks, or if you can't get the rights to certain individual songs because of shared copyright or something, solve the problem by making the album available only as a complete album, or only by track, or don't include the questionable tracks at all-- only alter the standardized price as a very last resort, and never go above $9.99.) And every single piece of music in the iTunes Music Store is subject to the exact same stipulations as far as CD burning goes: every song is freely burnable. No matter who it is. As many times as you want, as long as you aren't just making a playlist and then running off copy after copy (it stops you after ten of those). For all honest intents and purposes, it's unlimited once you own the songs.

So it's with that egalitarian ideal in mind that Apple seems to have undertaken its long trek through the computer industry with the digital music revolution. First, the iPod and iTunes were both Mac-exclusive; and they weathered the usual storm of ridicule from people who assume that because it's Apple, it's got to be overpriced and crap. iPod People were sneered at as much as they were secretly admired. And gradually the ridicule gave way to longing.

But for that first phase, Apple wasn't selling to the Windows public. They knew what they were doing. They were selling a Mac premium, something that they knew the faithful would eat up en masse, something that would bring in an instant infusion of revenue. I've heard that the iPod is actually priced at a very tight margin-- the parts' individual cost add up to not much less than the retail price, which I guess speaks volumes about the quality of the merchandise-- but they still managed to foster a complete digital-music culture nearly overnight, starting in November of 2001. Those white earbuds, which you saw in a surprising number of ears, were a symbol of a sacred cult. You knew you were seeing another Mac user there across the mall, and many a knowing smirk and nod was exchanged.

During that first phase, Apple didn't just sell iPods to the Mac faithful, though-- they sold iPods by the handful to technophile early-adopters, all the people who used PCs but who weren't married to them; people bought iPods because they were just the coolest thing on the block, and then they bought Macs to go with them. After all, even at the outset, the iPod worked with third-party Windows utilities like EphPod and XPod-- but not amazingly well; and after wrestling with those tools for a while, no small number of Windows users broke down and bought an iBook or an iMac ("For my daughter", they usually said) to drive the iPod the way it was intended. I saw it happen five or six times right here in my own company. This was the period when you saw celebrities buying iPods and flashing them around on Wilshire Boulevard. The iPod was becoming a style statement, no matter what computer you used. And if you had the money for it, you became a Mac user in the bargain.

But eventually that stream of new-Mac revenue started to dry up, inevitably. There are only so many early-adopters in the world, after all, and over the course of 2002 the iPod wannabes-- the pseudoPods-- all came to market. SonicBlue. Archos. Creative. They all made their own "iPod-killers", often with bigger hard drives-- meaning they were physically bigger as well as having more capacity, because the competitors didn't adhere to the same standards of the newest and smallest drives and the most efficient mechanical design possible. That's how they were often able to undercut the iPod in price, and a few of them caught on. The iPod remained the reigning champ in its market segment, but it was now diluted-- and people started buying things like CD-R players (which you have to hold in your hand, horizontally, while you rock out on the streetcorner-- something that city dwellers everywhere seem perfectly willing to do), which were a much more ungainly solution... but cheap.

So Apple fired the second stage of the rocket.

The iPod was now Windows-compatible. True to form, it had exactly the same features as it had on the Mac; they went to great lengths to retool a version of MusicMatch Jukebox to support iPod autosyncing, and they made sure that all MP3s were organized according to ID3 tags rather than filename. Prices were identical. You needed a FireWire cable, even on the PC. But now Apple could market the iPod as being truly intended for the Windows market as well as the Mac, and the ad campaigns reflected this. Soon, the more cautious customers who had never considered the iPod before, because they knew it was only officially supported on the Mac, were sneaking in the doors of the Apple Stores to pick up iPods. Sure, they weren't buying their iPods with a side of iBooks anymore-- but some did, and the real benefit was in volume. By all accounts they sold an absolute pantload of iPods during this phase. It's at this time that the iPod entered the public lexicon; it started showing up in movies, TV shows, lifestyle ads for other products, marketing tie-ins (like with the VW New Beetle). Accessories appeared. The second generation of iPods came out, with PDA functionality that left the earlier models (like mine-- blah) in the dust. Windows users were now buying iPods on their own merits as standalone devices, not as "something that Apple makes but that weirdly doesn't require a Mac". The competition started to fade into the background again.

But then the iTunes Music Store happened, and suddenly the focus of Apple's digital music campaign was back on iTunes. And iTunes was Mac-only, still. Sure, it's a great concept, this store-- I mean, look at all that flat pricing, all those generous DRM terms, all that ease of use-- but it's still Mac-only.

For a time, this was not a handicap. For a time, the iTunes Music Store helped sell new Macs, just as the original iPod had. But Apple weathered more ridicule from the Wintel camp, from CEOs of rival startup music stores who scoffed at Jobs' obstinate refusal to play with 95% of the market. They saw their own jobs as being to "show Apple how it's done"-- BuyMusic.com illustrated the typical reaction with its vicious guitar-smashing ad campaign, and a dozen other companies rushed to bring out their own online music stores now that the labels were buttered up by Apple's foot-in-the-door contract agreements. (Many were able to negotiate more favorable deals with the other stores, which is why you have the weird price non-parity problem when you browse PureTracks.com or BuyMusic.com.) And all summer long, Apple quietly let its own store sell to the Mac faithful, and to the early-adopters who hadn't already been lured to the Mac fold by the original iPod. They reaped the fat off the bell curve as it rolled slowly past.

But eventually that income trickled off, as the competitors came online, and Apple lost its advantage of exclusivity and novelty. This was not unexpected; Apple had been planning the third stage of their assault long before, knowing that the time to push the button would come. And yesterday, it did. Out came iTunes for Windows.

They'd announced early on that they'd hoped to bring the iTunes Music Store to Windows. Right after the store originally opened in April, as a matter of fact. Partly this was to appease the investors, who weren't about to put up with another revolutionary advance that would only be enjoyed by a paltry few percent of the market; but partly it was just setting expectations in the market itself, letting people know that they could wait until the end of the year for a Windows version of this we-thought-of-everything-and-did-it-right service... or they could just buy a Mac and have it all right now. And many chose the latter.

If Apple had released iTunes 4 for the Mac and PC simultaneously, they would have been pulling a WorldTalk. They'd have eliminated the competitive advantage of the Mac, without getting anything for it in return. But by delaying the Windows release, they were able to pull in more Mac buyers who wouldn't otherwise have jumped ship, as well as to build up that all-important impression of being an exclusive company making premium products that were sort of mysterious and inscrutable. After all, that's where a lot of the Mac's mystique comes from-- its niche-market nature. Most PC users know of Macs as only an odd, luxury-priced, fringe computer platform-- and while they dismiss it for the most part as just some kooky "alternative" thing, or the AOL of the computer market, deep down they know there must be something someone's not telling them. What are all these Switch ads about? they ask. Why is there all this buzz about some freaky computer that nobody uses? What am I missing? And so there's genuine curiosity under all the dismissal.

iTunes is the first Windows application that Apple has committed itself to publishing since QuickTime; and as I've mentioned before a number of times, QuickTime is not the most dashing of ambassadors to the Windows side of the fence. It's widely regarded as being buggy, greedy with filename extension mappings, and annoying in its nag screens and TSR behavior. Valid concerns all, and I can hardly blame most Windows users from having a general reaction of "Eeww!" when they think of the Apple logo. To most, it's just some has-been company that makes weird niche computers, and this "QuickTime" software that nobody likes. Why would anybody buy a Mac in this day and age?

iTunes is the answer to all that, and that's why yesterday was so important for Apple. This is the first opportunity the company has to really make a positive impression on the Windows community-- to show Windows users that they're capable of a lot more than just QuickTime, and that they can in fact write software that Windows users might find palatable or even droolworthy. The iPod did that in its own way, but it's not software, it's not a computer-- so now it's iTunes' turn to make the case.

Apple has waited a long time before giving away the keys to the kingdom, as it were-- and they haven't even really done that, either. iTunes is hardly the only application that makes the Mac what it is, though it's certainly one of the best examples of it. It remains to be seen whether Apple will be able to justify bringing other apps to Windows-- like iPhoto, for instance, where there's a potential profit center in the photo-ordering and book-making functions, but not as much of a runaway hit as buying music already has proven to be. But in the meantime, they've committed to turning iTunes into their new "ambassador" app-- and doing it right this time.

That means being 100% feature-compatible across platforms. The Windows version isn't lacking a single feature that the Mac version has. Autosync? Yes. CD/DVD burning? Yes. AAC codecs and file locking? You betcha. Music sharing across platforms? Indeed yes. Rounded transparent window corners? Yup, they've got that too. The practical upshot is that there is nothing in iTunes that makes Windows users second-class citizens. In keeping with the philosophy of making sure everything is equal across the board-- either done 100% right, or not done at all-- iTunes for Windows is meant quite literally to be, in the words of the splash page, "the best Windows app ever". Glib, yes; smirking, yes; but with a kernel of self-effacing truth to it as well. Apple knows that Windows users view Apple as a snooty luxury-market vendor; but if they can play off that assumption, by coming across as kookily lofty and arrogant ("Hell froze over! We made a Windows app!") while at the same time providing a piece of software that's free and top-drawer and doesn't treat them like an untapped market for new Mac purchases (by giving them all of iTunes' feature set, instead of teasing them with a partial version and then entreating them to buy a Mac in order to get the real thing-- "Hup! Whoah, almost got it... Whup! Noo, gotta jump higher... 'cmon, boy..."), they might just be able to win a set of hearts and minds that would have been otherwise unavailable.

This development brings the Apple logo to the Windows user's desktop in a context that covertly leverages Apple's strengths while subtly springboarding off its image weaknesses. If the Windows iTunes becomes a popular enough download, as likely found on a Windows user's desktop as WinAmp, then Apple will have won the most difficult battle in the whole effort to gain back their lost market share: the battle of logo association. If they can make it so that most Windows users have a positive reaction to the Apple logo, rather than the negative one they have now (deservedly so or not), the rest of their marketing job becomes infinitely easier. It's way easier to sell to someone who thinks of you as a maker of good products than to someone who thinks you ought to have died long ago.

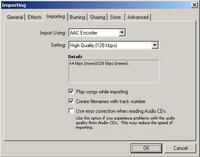

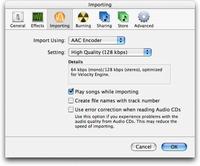

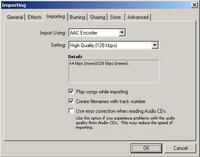

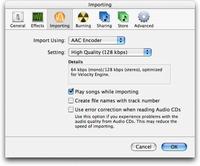

And, of course, if anybody should happen to wander into an Apple store, and notice the subtle differences in cosmetics that do exist between the Windows and Mac versions of iTunes...

... well, they're welcome to buy a Mac, y'know. Hey, how bad could it be?

By the way-- in the two comparative screenshots above, notice how the Windows version has the OK button on the left and Cancel on the right, which is the Windows standard but backwards from the way the Mac does it (Apple's UI guideline is to put the "default" action at the extreme right, close to the "forward" margin and near your right hand). Also, the Windows screenshot says "filenames", as is more commonly used in Windows, whereas the Mac one says "file names". Don't think that isn't intentional; they really do pay attention that closely to detail. And they really do commit to a set of UI guidelines for a given platform, even when they don't agree with them.

UPDATE: According to AtAT, the price breakdown of this whole venture is very intricate and profit-directed:

So how, you ask, does Apple expect to make any money selling music to the notoriously cheapskate Wintel market? Answer: they don't. CNET reports that Phil "Gilligan, Drop Those Coconuts" Schiller freely admits that, while the iTMS is "close to profitability," it's "still losing money" overall-- and even when it does squeeze into the black, Apple "doesn't have any illusions that it can make great profits from selling songs over the Internet." In short, says Phil, "the iPod makes money. The iTunes Music Store doesn't." Wow. The last time we encountered anything that blunt, someone was swinging it at our heads.

So, let's think about this for a minute: if Apple (who had a massive infrastructure already in place for the delivery of scads of data over the 'net) can't make a profit on 99-cent songs even when selling in the volume of millions, what hope is there that legal services offering cheaper tunes will stay in business long enough to compete? In other words, unless the record labels decide to lower their wholesale prices to song resellers like Apple, 99 cents is probably the rock-bottom sustainable price we'll see for a while-- and Apple isn't even expecting to make money on the songs at that price. As company execs have stated before, the whole point of the iTMS is to sell iPods.

Incidentally, this ties in directly to another iTMS complaint we keep seeing from Wintel folk: if you buy iTMS songs and you want to take them with you, you "have to buy an iPod." And yes, that's 100% true, at least for now. But guess what? If you're not the sort of Wintel user who'd buy an iPod, Apple doesn't want you as an iTMS customer anyway; unless you also buy that iPod (and maybe eventually a Mac), any songs you purchase from Apple are probably just costing the company money. Let's be clear about this: Apple isn't going after the whole Wintel market with iTunes. It's going after the subset of Windows users who happen to have a little taste, and (more importantly) a little money to spend on iPods and other nifty (and profitable) stuff.

Wow. Kinda sobering, that... but now that the pieces are all in play, we can expect a major shakeout to start happening.

|

|

Brian Tiemann

Brian Tiemann